If you'll forgive me for my coarse language in an academically themed blog. I was merely following Dr. Sexson's assignment to make the first sentence of my new entry to be eye-catching and hooking.

Shakespeare's All's Well That Ends Well is a play that requires a bit of reflection and processing after reading it. It isn't the crowdpleaser that Midsummer Night's Dream is, nor does it have the appealing complexity of As You Like It. It's a real challenge to really make sense out of, and the conventions of some of the characters' decisions and personalities at times made me feel like I was reading a Bertolt Brecht play rather than a work of Shakespeare. Brecht, a 20th century playwright, wrote his works with the "alienation effect" in mind--which allows the play to function in a way that the audience member never has a complete "suspension of disbelief", and the whole time is a critical observer of the course of events on stage.

Northrop Frye's essay, "The Argument of Comedy", sheds light on why the play just isn't as resonant as Shakespeare's other comedies. All's Well That Ends Well is classified as "New Comedy", yet Shakespeare's twists on the standard conventions lead it to play out in outright confusing ways. Frye observes that the role of the senex (the old man/father) is reversed in this play. Whereas the father figure usually opposes the love affair in question (as in Egeus in Midsummer Night's Dream), the senex in this case, being the King, forces Bertram to marry Helena. As this concerns to storytelling and character development, the dynamic between these two "lovers" is a jarring one.

Why Helena, a lowly but gifted daughter of a physician, would be attracted to Bertram to the point that she goes through such extensive measures to woo him does adhere to our definition of courtship. Bertram is not a likable or relatable character. Some would say that he is revolting and detestable. And yet, when he rather coldly tells her that she will never truly be his wife via letter (probably the Shakespearen equivalent to a text message breakup), she still pursues him by attempting to secure his ring and his child, per his challenge. It's rather off-putting how much effort she goes through to marry below her in terms of her mate's moral character.

The convention of New Comedy pertaining to the wedding at the end is still intact, but once again, it feels out of place. Is it realistic to expect Bertram to accept Helena as his wife after he has been deceived with the elaborate "bed switching" plot?

If she, my liege, can make me know this clearly, / I'll love her dearly - ever, ever dearly. (V.3)It's a problematic situation, indeed. Realistically, why wouldn't Betram be further repulsed by Helena's troubling measures to woo him? By today's standards, the way that these two work together would be a compelling case study of a very unhealthy relationship. Bertram's submission to Helena's proposal is really the strongest point in which any sort of redeeming quality is apparent in his character, and it rings false.

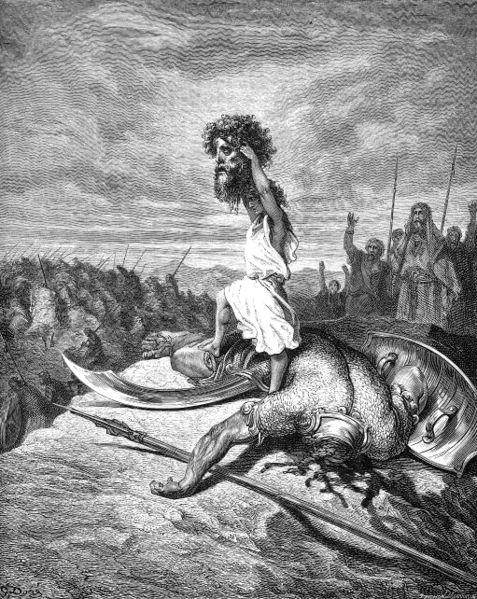

Perhaps Shakespeare could have further skewed the conventions of New Comedy by having this realization on Bertram's part being quashed by Helena's realization that she deserves better. In a final act, she turns the tables and rejects him. Thus, the end would have no obligatory wedding that is a standard part of the New Comedy formula, but the majority of the cast would be present for what many readers/audience members would call justified humiliation. Sadistic? Probably. But to me, it makes more sense. Look at the myth of Venus and Adonis: the female is in the position to pursue the male. Adonis ends up meeting a brutal fate, and while this is far from comedic, one can argue that his rejection of the love of a goddess set him up for an untimely death. He did nothing to deserve her love, so why should he get it? In the case of Bertram, why the sudden change in heart?

What we're left with instead is a message that you can still be a terrible human being and wind up with a girl whom you've done nothing to deserve (unless being beaten at your own game of deception and impossible riddles makes you qualified). That's not to say that the word play and innuendos (as mentioned by Anne) don't give the play a humorous touch that makes it an interesting and clever play. Clever, but confusing... and not strictly in the Shakespearian sense.

Test tomorrow. Bring it on!