When discussing works of tragedy in class yesterday, Dr. Sexson made a great argument that if you walk out of a theater and simply say "Now THAT was depressing!", then there is either something wrong with you or what you just saw. I immediately thought of three of my favorite films, which are all modern tragedies that are so utterly brilliant and devastating that I know that William Shakespeare would have given his seal of approval... and I can't recommend them enough.

These films are all part of The Vengeance Trilogy by Korean director Park Chan-wook, who said that Shakespeare is indeed a profound influence on his work. A trailer for each film...

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Don't let the Americanized movie trailer fool you. This film is at such a slow, wrenching pace that it literally makes your skin crawl. This one might be the most Lear-esque out of the trilogy--an absolutely devastating masterpiece.

Oldboy is easily one of the best films of the last decade, and might be one of the greatest films ever made. Period. Don't let anyone ruin the twist for you. It also happens to have one of the best fight scenes of all time, and a scene where a live squid is eaten whole (no joke).

Lady Vengeance. Perhaps the most emotionally disturbing of the three. Be forewarned, there is some really violent content involving children in this film. I also just realized that it's another version of the Demeter myth--mother and daughter reunited, even though the Lady Vengeance herself may not find peace. See it to see why!

All three of these are streaming on Netflix instant (though I think Oldboy is dubbed--AVOID IT), and if you want to see modern tragedy done in a highly entertaining, emotionally gut-wrenching, and utterly beautiful way then look no further than the Vengeance Trilogy.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Monday, April 25, 2011

The Gods Must Be Crazy (FINAL PAPER!)

Mything Shakespeare:

Shakespeare and Divine Visitation

The gift of rapturous love and the maddening sense of isolation ostensibly stem from the same source—that is, according to William Shakespeare. To trace the origins of any of Shakespeare’s characters’ consuming adoration of another, or descent into mental decay, one must only look to the gods and beings from the heavens that cause such sensations through their intervention. Myth pervades the works of Shakespeare, whose most enduring works of any genre overflow with allusions to the divine, however distant these allusions may be at times. The presence—or absence—of otherworldly beings has repercussions that prove pivotal to the fate of the characters in Shakespeare’s own mythology. Whereas divine visitation sets the stage for a strictly comedic resolution and inspiration, the absence or rejection of this godly presence typically results in characters meeting a tragic end.

Of the works studied this semester, the most striking example of divine presence as a unifying force in the universe of the play is found in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. While the initial setup of Hermia facing death if she does not choose a suitor to her father’s liking is one that bears tragic possibilities, the comedic conclusions reached are those of the will of Oberon, the fairy king. Taking place in a cross-section of the human world (Athens) and the land of fairies (the wood), the two interact in such a fashion that the divine forces manipulate the course of events to their liking. However, this otherworldly influence does not make itself known to the main players of the story. As explored in Northrop Frye on Shakespeare, the author explains that though Theseus, king of Athens, overrules the will of Hermia’s father, it is really Oberon and the other fairies who, through the magical orchestration of the two couples of young lovers, overrule the authority of the king (40).

Peter Quince, or Bottom, stands out amongst the cast of characters as the only person to have knowingly bridged this gap between the worlds of fairies and humans. An object of love and adoration for the fairy queen, Titania, Bottom emerges from the experience inspired and gives what Frye calls “one of the most extraordinary speeches in Shakespeare”. However lowly and unrefined his character is portrayed in the play in comparison to the lovers or the ruling class, his spirit is filled with a glowing perspective that Peter Quince describes as a dream—and a “bottomless” dream at that. The specific details of this dream are not definite, but Frye argues that he comes “closer to the centre of this wonderful and mysterious play than any other of its characters” (50). Unseen yet pervasive divine power, however chaotic, unifies the action of the play to a fitting, celebratory end.

Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy As You Like It is unique in that its inclusion of divine visitation is often omitted in performance due to the contrived nature of the occurrence. What began as a problematic play with feuding brothers, banishments, and betrayal ends in classic comedic fashion with the wedding of four couples. Hymen, the god of weddings, oversees this ceremony and ensures that separated family members are reunited and that all old sins amongst brothers are atoned. His presence is likewise a comedic, if arguably unnecessary, unifying plot point that enforces a comedic end.

This play also explores the notion of isolation from such godly forces. The character of Jaques in As You Like It gives a bleak speech that, as discussed in class lecture, depicts a world without myth. In Act II, Scene 7, his ponderings of the world as a stage and “the men and women merely players” walk through various phases in the life of men—ending with the individual living in “mere oblivion…sans everything.” This grim analysis of life betrays the comedic nature of the play, yet is remarkably telling when reflecting on Shakespeare’s more tragic works, in which the presence of the divine is absent.

The pre-Christian setting of King Lear is a barren landscape of gods and forces that the cast of characters does not understand. From the references to mythology throughout the play, it is apparent that the mindset amongst Lear and others is that of a deist mentality—that some form of a god is there, but does not interfere with matters of the earthly realm. According to Frye, it’s absolutely appropriate that this tragic story is pre-Christian, as the story behind Christianity is one of the salvation and redemption of man, which is comedic in its structure (102). Though no actual divine visitation occurs, there are suggestions of a detached influence. The world in King Lear is filled with “impotent or nonexistent gods” that present themselves as forces of Nature or fate (107). For example, the storm in Act III acts as a force of Nature that is representative of a sort of Old Testament “crossing of the Red Sea in reverse” (114). The vague, mysterious qualities of the otherworldly depicted in this tragedy yield only madness and despair as all characters meet a savage fate.

When taking into account the absence of the divine in King Lear, a similar tragic end occurs in Shakespeare’s narrative poem Venus and Adonis. In what Jonathan Crewe prefaces as “an ‘early’ representation of sexual harassment”, the love of Venus, the goddess of love, is rejected by the mortal Adonis (Pelican Shakespeare, 5). Borrowing heavily from Ovidian mythology, the epic poem resonates throughout the Shakespearean canon as what Dr. Sexson described as his “consuming myth”. The refusal of Adonis to become Venus’ lover speaks to a disparity between the love of the divine and the capability of humans to experience it. Adonis’ tragic slaughter by the boar in a hunting accident, while mourned by Venus, was nonetheless a result of his reluctance to embrace the divine love of the goddess—Shakespeare having implicated Venus in the death of the man (5).

The adage that man needs myth to survive is not a new one, and it is through the works of Shakespeare that we might come closer to understanding why these stories of the divine resonate so deeply. The rejection of such myth is commonplace in the current times, often disregarded as irrelevant. Yet if there’s one thing that can be learned from Shakespeare is that the inspiration from story and myth is a blessing that can be experienced by any one of us. In my mind, dismissing these divine gifts of the mind can’t be described as anything other than tragic.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Mighty Aphrodite

The group presentations are kicking off tomorrow, and the more I look at the play that I was assigned with my group, the more interested I am in it. Othello is awesome, folks. Really.

Some of this will probably make way in the presentation that we're giving, but some of the secondary criticism about Othello has brought a lot out of the play--more than the themes of race that has arguably given this play the longevity that it possesses. One of the more interesting points brought up in the text's intro by Russ McDonald in our big red tome (and also in a similar intro by Walter Cohen in a different edition) is the power of love.

We've talked a lot about consuming myths in this class, and I never really thought I would find it in Othello. There's the drama, the deceit, and the passion that was promised, but I did not expect to find the Venus and Adonis myth transposed into this setting. Granted, it's a bit more displaced and further removed from mythology than many of the other plays we examined, but it nonetheless proved very interesting. It's always great when you have multiple lenses through which to view a timeless story.

Some of this will probably make way in the presentation that we're giving, but some of the secondary criticism about Othello has brought a lot out of the play--more than the themes of race that has arguably given this play the longevity that it possesses. One of the more interesting points brought up in the text's intro by Russ McDonald in our big red tome (and also in a similar intro by Walter Cohen in a different edition) is the power of love.

Othello teeming with jealousy as Iago plants seeds of doubt and jealousy,

from the film version. Laurence Fishburne and Kenneth Branagh are amazing.

The real meat of this play and the downfall of the central tragic figure doesn't really revolve around political futures (as in King Lear or Hamlet, for example). What undoes the character of Othello is love and jealousy. The forces that motivate Iago to set this plot into motion may be rooted in selfish attempts for personal (and somewhat political) gain, but the power of that seed of envy and suspicion that he plants in Othello overtakes the man in an utterly all-consuming, complete fashion. The power of the love, or the goddess of love, be it Venus, Aphrodite, or any version of said goddess, is one that can cast anyone to the heavens or down into the depths of hell. It's an incredible portrait of an energy that is often only associated with the positive.

We've talked a lot about consuming myths in this class, and I never really thought I would find it in Othello. There's the drama, the deceit, and the passion that was promised, but I did not expect to find the Venus and Adonis myth transposed into this setting. Granted, it's a bit more displaced and further removed from mythology than many of the other plays we examined, but it nonetheless proved very interesting. It's always great when you have multiple lenses through which to view a timeless story.

Monday, April 11, 2011

The Lighter Side of "Othello"...

Note: this is a bit PG-13 rated, but a great satire of Othello.

Figured this wouldn't fly in the group presentation, but I needed the class to see it somehow!

Figured this wouldn't fly in the group presentation, but I needed the class to see it somehow!

Monday, April 4, 2011

Where To Begin?

The more I consider the assignment of a Shakespeare presentation, the harder it gets to brainstorm a topic. On one hand, Shakespeare is incredibly broad in scope that allows for just about any kind of exploration. However, what is there to say about his works that nobody else has said before? When you consider how the persistence of "myth" is also a big topic for discussion, that means a little bit more digging.

Consider this a stream of consciousness brainstorming blog. Here it goes...

- Consuming myths--Shakespeare had them, his characters have them, and we all have them. Which consuming myth can I explore as it relates to the works we have studied in class?

- The Green World--It isn't always as perfectly spelled out in his plays as it is in A Midsummer Night's Dream or the pastoral As You Like It, but the presence (or absence) of it always plays a part in the universe in which the characters live, even if not explicitly stated.

- There always seems to be a fatal flaw that afflicts a mortal who is given blessings and grace from divine beings that makes them so close to perfection, and yet they experience an utterly complete demise that they remain just slightly out of arm's reach of such status. Some characters are looked upon favorably in a similar fashion by having great fortune, but experience a complete downfall (Arguably: Antony and/or Cleopatra, Othello, which I read in my group). I'm sure there's a word or phrase for this complex (if you know it, you can write it in the comment box!).

- What happens when the divine beings cross over into the mortal world? (Consider: A Midsummer Night's Dream, As You Like It, Cymbeline) Also worth looking at--does the stark and bleak world of, say, King Lear, have anything to do with the fact that there are no gods that look favorably upon the players? (The line about the gods causing humans to suffer for sport)

- The question of displaced myth--that's kind of all that I got for that one for some reason.

- Stratification of people/gods and how it plays into Shakespeare.

More to come, let's hope?

Monday, March 28, 2011

Making Sense of Cymbeline

Good luck.

With the title of my blog, I don't mean to suggest that the play's action itself doesn't make sense... In fact, I'm amazed that I've never heard of this play before I took this class. I found the characters, the action, the dialogue, and the story itself to pack a big punch. Each character, even the villains, are given such incredible detail and nuance to their personality--many of the more tragic characters are redeemed in the end (thanks to Ashley Arcel for pointing that out so well in her blog entry). And, of course, since college-aged students love sexual innuendo, I have to say that the dialogue in this play is masterful and quite filthy. I didn't even need to look at the footnotes to tell that Cloten was a sick, perverted bastard!

I am not yet able to completely describe how Cymbeline makes sense in the grand scheme of Shakespeare's romances as far as its relation to the mythic, as I have not yet completed the rest of them. My initial impression of this romance, as it compares to some of Shakespeare's other very, very dark tragedies (especially King Lear) is that while they maintain a similar arc, the ending tends to share more in common with the present-day narrative in American films.

This doesn't apply to all works of the present day, but it seems as if audiences are willing to accept just about any insane, dark, twisted elements in a story so long as things turn out all right in the end. If a character has been through hell, then they better make it out alive. Not to disparage the end of Cymbeline as a "Hollywood ending" (even though everything fell completely into place quite conveniently), but the characters we know and love make it out just fine. By and large, I think it works. Perhaps if Cymbeline ended in a blood bath like King Lear or Hamlet, its reputation would be more prominent because of that (I have no way of knowing, just a hunch).

Based on my current impressions on Cymbeline, what seems out of place when trying to categorize it as more of a comedy versus a drama makes for an interesting product, nonetheless. It's amazing how much of a model this is for what we see as a standard for entertainment today. A problematic set-up where everything that can possibly go wrong does, and in the end the difficulties are reconciled in such a way that it doesn't feel too out of place. Graned, the god Jupiter makes an appearance, but it felt okay with me. After all, deus ex machina has become so common in today's popular culture that most non-English majors (and even plenty who are) could see one without even knowing it.

Next up: Pericles.

With the title of my blog, I don't mean to suggest that the play's action itself doesn't make sense... In fact, I'm amazed that I've never heard of this play before I took this class. I found the characters, the action, the dialogue, and the story itself to pack a big punch. Each character, even the villains, are given such incredible detail and nuance to their personality--many of the more tragic characters are redeemed in the end (thanks to Ashley Arcel for pointing that out so well in her blog entry). And, of course, since college-aged students love sexual innuendo, I have to say that the dialogue in this play is masterful and quite filthy. I didn't even need to look at the footnotes to tell that Cloten was a sick, perverted bastard!

I am not yet able to completely describe how Cymbeline makes sense in the grand scheme of Shakespeare's romances as far as its relation to the mythic, as I have not yet completed the rest of them. My initial impression of this romance, as it compares to some of Shakespeare's other very, very dark tragedies (especially King Lear) is that while they maintain a similar arc, the ending tends to share more in common with the present-day narrative in American films.

This doesn't apply to all works of the present day, but it seems as if audiences are willing to accept just about any insane, dark, twisted elements in a story so long as things turn out all right in the end. If a character has been through hell, then they better make it out alive. Not to disparage the end of Cymbeline as a "Hollywood ending" (even though everything fell completely into place quite conveniently), but the characters we know and love make it out just fine. By and large, I think it works. Perhaps if Cymbeline ended in a blood bath like King Lear or Hamlet, its reputation would be more prominent because of that (I have no way of knowing, just a hunch).

Based on my current impressions on Cymbeline, what seems out of place when trying to categorize it as more of a comedy versus a drama makes for an interesting product, nonetheless. It's amazing how much of a model this is for what we see as a standard for entertainment today. A problematic set-up where everything that can possibly go wrong does, and in the end the difficulties are reconciled in such a way that it doesn't feel too out of place. Graned, the god Jupiter makes an appearance, but it felt okay with me. After all, deus ex machina has become so common in today's popular culture that most non-English majors (and even plenty who are) could see one without even knowing it.

Next up: Pericles.

Monday, March 21, 2011

Antony and CLEOPATRA (IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS)

"Success in heroic love being impossible, better to fail heroically than to succeed in mediocrity". -- Northrop Frye

Antony and Cleopatra is sprawling. A huge cast of characters, numerous locations, a very fragmented and fast-paced middle portion with plenty of scenes, and very richly developed main players. Though Antony is no slouch, the real emphasis, of course, is on Cleopatra.

I admit that for as realistic and non-mythological as this play is in comparison to the other plays we have studied, a lot of it went over my head. I'll be lucky if I even got the 24% of Shakespeare that Dr. Sexson equated to the 89% of Stephen King. Regardless, there's a lot to be said about the titular characters. Inherent in the play's setting is a lot of dichotomy between Antony and Cleopatra and the worlds they live in. As mentioned in class, the Roman and the Egyptian societies have vastly different characteristics-- white versus black, masculinity versus femininity , reason versus passion, fluid and indistinct versus fixed, and many, many more.

As mentioned in Northrop Frye's look at Antony and Cleopatra, the character of Antony does not adhere to one society's tendencies completely. He finds himself drifting back and forth between the world of desire and love of Cleopatra's Egypt and the politics and heroism of Caesar's Rome. Frye noted that Antony has a very interesting place on the typical stratification of literary characters, which looks a little something like this:

- Divine beings, or a hero descended from the gods.

- Romantic heroes and lovers. Human, but not subject to ordinary limitations.

- Kings and other commanding figures in social or military authority.

- The ordinary folk.

- Unfortunate people, assumed to possess less freedom that us.

(132-133)

On the other hand, you have Cleopatra--a much more colorful character around whom the play revolves.. and there's no doubt about the fact that she knows it, too. The discussion continued ad infinitum about the character of Cleopatra very much embodying drama with every grand gesture and emotional tirade. As queen of Egypt, she very much already is a goddess (134)--so why shouldn't she act like one?

I found the fact that her dramatic style being associated with the constant presence of an audience of some sort present with her to create an interesting but confusing portrait of her. As big as her emotions are played out, as violently as she treats the messengers who displease her, as dramatic as her death really is, do we really know anything about the real Cleopatra? To me, there always seemed to be a sense of artifice in every action, even if the emotion behind it was one of sincerity.

With Cleopatra that outrageousness and power create a figure so unmistakably her that, as Frye said, she fully expected to maintain her kingdom, her man, and her goddess persona in the afterlife. I would say that her ferocity, passion, and taste for the theatrical coupled with Antony's spectacular (though failed) attempt at maintaining love with Cleopatra makes for the stuff of legends. Shakespeare certainly has a way of escalating the business of humans to mythic proportions.

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Final Thoughts on "Lear"

Before I dig into Antony & Cleo, I thought I'd get this Lear business wrapped up.

My secondary reading for this class is Frye's On Shakespeare book, which has a lot of fascinating things to say about King Lear, some of which was covered in class. Specifically, the recurrence of the words "nothing", "nature", and "fool". I found the concept of nature to be very interesting... or for this occasion we'll give it a capital "N".

Lear takes place in pre-Christian times, as we know, but the concept of Nature having a tiered structure is a very compelling one that places a lot of Christian/mythic dimension to the story. As Frye described Nature, it has four levels:

1. Heaven (or wherever God lives), represented by the sun and moon (and the stars, perhaps? Such as Edmund's contemplation of his "baseness" to the stars)

2. "Unfallen" Nature (such as the Garden of Eden)

3. "Fallen" Nature (in which animals survive well enough while humans struggle)

4. The demonic world (which may represent itself in the vile elements of Nature, such as the storm in the play)

Taking into account the notion of "displaced myth", Frye goes deeper in describing what the world of Lear is like... There is no God or gods but only occasionally deified representations, the "unfallen" Nature exists only in the goodness of select characters, the "Fallen" existence of men renders them animals, and that the "hellish" elements are found in the madness of Lear. It's an incredibly grim, bleak world indeed.

Reading King Lear comes as a bit of a shock considering that the three previous plays we have examined are comedies, and rather light-hearted ones. The Green World of A Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It is nowhere to be found. The very idea of it seems like it's just a very foggy notion, an absolute impossibility. The only remnants of it, found in the love of Cordelia or the loyalty of Kent, are not realized or embraced until the devastation has already taken place. Even so, the love that he has for Cordelia and the reason behind it is really just "nothing", or at least it exists for no real reason, as Frye explains. It's an interesting and disturbing thought--a world of a fallen, animalistic experience that sends Lear spiraling into madness, and even the scarce love that he can find, however sincere it is, exists for no reason... perhaps that's what consumes Lear. The idea of "nothing".

My secondary reading for this class is Frye's On Shakespeare book, which has a lot of fascinating things to say about King Lear, some of which was covered in class. Specifically, the recurrence of the words "nothing", "nature", and "fool". I found the concept of nature to be very interesting... or for this occasion we'll give it a capital "N".

Lear takes place in pre-Christian times, as we know, but the concept of Nature having a tiered structure is a very compelling one that places a lot of Christian/mythic dimension to the story. As Frye described Nature, it has four levels:

1. Heaven (or wherever God lives), represented by the sun and moon (and the stars, perhaps? Such as Edmund's contemplation of his "baseness" to the stars)

2. "Unfallen" Nature (such as the Garden of Eden)

3. "Fallen" Nature (in which animals survive well enough while humans struggle)

4. The demonic world (which may represent itself in the vile elements of Nature, such as the storm in the play)

Taking into account the notion of "displaced myth", Frye goes deeper in describing what the world of Lear is like... There is no God or gods but only occasionally deified representations, the "unfallen" Nature exists only in the goodness of select characters, the "Fallen" existence of men renders them animals, and that the "hellish" elements are found in the madness of Lear. It's an incredibly grim, bleak world indeed.

Reading King Lear comes as a bit of a shock considering that the three previous plays we have examined are comedies, and rather light-hearted ones. The Green World of A Midsummer Night's Dream and As You Like It is nowhere to be found. The very idea of it seems like it's just a very foggy notion, an absolute impossibility. The only remnants of it, found in the love of Cordelia or the loyalty of Kent, are not realized or embraced until the devastation has already taken place. Even so, the love that he has for Cordelia and the reason behind it is really just "nothing", or at least it exists for no real reason, as Frye explains. It's an interesting and disturbing thought--a world of a fallen, animalistic experience that sends Lear spiraling into madness, and even the scarce love that he can find, however sincere it is, exists for no reason... perhaps that's what consumes Lear. The idea of "nothing".

Thursday, March 3, 2011

What You Need

Finding a universal "need" is definitely a difficult task. For me, one personal "need" is the Internet. It's funny that I blog about it on my own computer when there are people around the world who don't even know where their next meal will be coming from.

I did an interesting exercise with my coworkers lately that explored what we valued the most. We each noted the four people, memories, things, and values in our lives that we valued and needed the most. As the exercise progressed, we eliminated items from the dock--once they were gone, they were theoretically out of our lives. I found it easy at first, thinking "OK, I could really do without my computer in the grand scheme of things," or "As much as I love my dog I would still be me without him." Eliminating the list down to just ONE component was surprisingly emotional and eye opening. Taking people out of your life was something that was extraordinarily difficult for me. So, what was I left with? My mom--no matter how I look at my life, all of my values and abilities are in some way rooted to what she taught me and how she raised me.

It's a fascinating exercise that shows what you hold closest to you. What was first to go for me were things, and when I had to cut people out of my life then I was hard pressed to do so. I don't think it's presumptuous at all for me to say that everybody, across the board, no matter what-- needs people. It's a broad statement and those of you who are reading it are probably saying, "Well, duh."

While this may seem like a heavy-handed way to include Shakespeare into this pretty personal blog post, look at what happens to Lear's character. He isolates himself from those who love and care for him (Kent and Cordelia), investing his love and energy into people who reject him. Truth be told, Lear is no saint--his brashness in inflicting punishment on the ones who love him too much to see him do something stupid is evidence of that. If it's the cruelty of the people who betrayed him that sets him on the road to madness, it's the death of his daughter Cordelia that finally kills him. Pure, unconditional love lost forever, and indirectly by his doing nonetheless.

I find myself to be a fairly optimistic person when it comes to dealing with people. In spite of the cruelty that humans are capable of, the goodness that is potential within everyone far outweighs whatever flaws we may have as human beings. Without good people, we would be lost. A life separated from that limitless, unconditional source of love and fellowship is hardly a life at all.

I did an interesting exercise with my coworkers lately that explored what we valued the most. We each noted the four people, memories, things, and values in our lives that we valued and needed the most. As the exercise progressed, we eliminated items from the dock--once they were gone, they were theoretically out of our lives. I found it easy at first, thinking "OK, I could really do without my computer in the grand scheme of things," or "As much as I love my dog I would still be me without him." Eliminating the list down to just ONE component was surprisingly emotional and eye opening. Taking people out of your life was something that was extraordinarily difficult for me. So, what was I left with? My mom--no matter how I look at my life, all of my values and abilities are in some way rooted to what she taught me and how she raised me.

It's a fascinating exercise that shows what you hold closest to you. What was first to go for me were things, and when I had to cut people out of my life then I was hard pressed to do so. I don't think it's presumptuous at all for me to say that everybody, across the board, no matter what-- needs people. It's a broad statement and those of you who are reading it are probably saying, "Well, duh."

While this may seem like a heavy-handed way to include Shakespeare into this pretty personal blog post, look at what happens to Lear's character. He isolates himself from those who love and care for him (Kent and Cordelia), investing his love and energy into people who reject him. Truth be told, Lear is no saint--his brashness in inflicting punishment on the ones who love him too much to see him do something stupid is evidence of that. If it's the cruelty of the people who betrayed him that sets him on the road to madness, it's the death of his daughter Cordelia that finally kills him. Pure, unconditional love lost forever, and indirectly by his doing nonetheless.

I find myself to be a fairly optimistic person when it comes to dealing with people. In spite of the cruelty that humans are capable of, the goodness that is potential within everyone far outweighs whatever flaws we may have as human beings. Without good people, we would be lost. A life separated from that limitless, unconditional source of love and fellowship is hardly a life at all.

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

King Lear in Film: Kurosawa's RAN

I cannot recall how many direct (or indirect) adaptations of King Lear I've encountered, but one that sticks out in my mind is legendary filmmaker Akira Kurosawa's Ran (pronounced RON). It's essentially Shakespeare's play set in feudal Japan.

The trailer doesn't quite do justice to this film, which is quite a masterpiece. However, I will include it because our favorite animal makes an appearance. I didn't even notice it until now! THE BOAR!

Here's another look at it with commentary from critic A.O. Scott. It doesn't touch too much on how it's an adaptation of King Lear, and I'll admit that it's been a few years since I've watched it, but what I remember is an incredible story of the fall of an "ailing king". Highly recommended.

The trailer doesn't quite do justice to this film, which is quite a masterpiece. However, I will include it because our favorite animal makes an appearance. I didn't even notice it until now! THE BOAR!

Here's another look at it with commentary from critic A.O. Scott. It doesn't touch too much on how it's an adaptation of King Lear, and I'll admit that it's been a few years since I've watched it, but what I remember is an incredible story of the fall of an "ailing king". Highly recommended.

Wednesday, February 23, 2011

"All's Well", I Suppose

Sometimes, it pays to be a complete and utter dipshit.

If you'll forgive me for my coarse language in an academically themed blog. I was merely following Dr. Sexson's assignment to make the first sentence of my new entry to be eye-catching and hooking.

Shakespeare's All's Well That Ends Well is a play that requires a bit of reflection and processing after reading it. It isn't the crowdpleaser that Midsummer Night's Dream is, nor does it have the appealing complexity of As You Like It. It's a real challenge to really make sense out of, and the conventions of some of the characters' decisions and personalities at times made me feel like I was reading a Bertolt Brecht play rather than a work of Shakespeare. Brecht, a 20th century playwright, wrote his works with the "alienation effect" in mind--which allows the play to function in a way that the audience member never has a complete "suspension of disbelief", and the whole time is a critical observer of the course of events on stage.

Northrop Frye's essay, "The Argument of Comedy", sheds light on why the play just isn't as resonant as Shakespeare's other comedies. All's Well That Ends Well is classified as "New Comedy", yet Shakespeare's twists on the standard conventions lead it to play out in outright confusing ways. Frye observes that the role of the senex (the old man/father) is reversed in this play. Whereas the father figure usually opposes the love affair in question (as in Egeus in Midsummer Night's Dream), the senex in this case, being the King, forces Bertram to marry Helena. As this concerns to storytelling and character development, the dynamic between these two "lovers" is a jarring one.

Why Helena, a lowly but gifted daughter of a physician, would be attracted to Bertram to the point that she goes through such extensive measures to woo him does adhere to our definition of courtship. Bertram is not a likable or relatable character. Some would say that he is revolting and detestable. And yet, when he rather coldly tells her that she will never truly be his wife via letter (probably the Shakespearen equivalent to a text message breakup), she still pursues him by attempting to secure his ring and his child, per his challenge. It's rather off-putting how much effort she goes through to marry below her in terms of her mate's moral character.

The convention of New Comedy pertaining to the wedding at the end is still intact, but once again, it feels out of place. Is it realistic to expect Bertram to accept Helena as his wife after he has been deceived with the elaborate "bed switching" plot?

Perhaps Shakespeare could have further skewed the conventions of New Comedy by having this realization on Bertram's part being quashed by Helena's realization that she deserves better. In a final act, she turns the tables and rejects him. Thus, the end would have no obligatory wedding that is a standard part of the New Comedy formula, but the majority of the cast would be present for what many readers/audience members would call justified humiliation. Sadistic? Probably. But to me, it makes more sense. Look at the myth of Venus and Adonis: the female is in the position to pursue the male. Adonis ends up meeting a brutal fate, and while this is far from comedic, one can argue that his rejection of the love of a goddess set him up for an untimely death. He did nothing to deserve her love, so why should he get it? In the case of Bertram, why the sudden change in heart?

What we're left with instead is a message that you can still be a terrible human being and wind up with a girl whom you've done nothing to deserve (unless being beaten at your own game of deception and impossible riddles makes you qualified). That's not to say that the word play and innuendos (as mentioned by Anne) don't give the play a humorous touch that makes it an interesting and clever play. Clever, but confusing... and not strictly in the Shakespearian sense.

Test tomorrow. Bring it on!

If you'll forgive me for my coarse language in an academically themed blog. I was merely following Dr. Sexson's assignment to make the first sentence of my new entry to be eye-catching and hooking.

Shakespeare's All's Well That Ends Well is a play that requires a bit of reflection and processing after reading it. It isn't the crowdpleaser that Midsummer Night's Dream is, nor does it have the appealing complexity of As You Like It. It's a real challenge to really make sense out of, and the conventions of some of the characters' decisions and personalities at times made me feel like I was reading a Bertolt Brecht play rather than a work of Shakespeare. Brecht, a 20th century playwright, wrote his works with the "alienation effect" in mind--which allows the play to function in a way that the audience member never has a complete "suspension of disbelief", and the whole time is a critical observer of the course of events on stage.

Northrop Frye's essay, "The Argument of Comedy", sheds light on why the play just isn't as resonant as Shakespeare's other comedies. All's Well That Ends Well is classified as "New Comedy", yet Shakespeare's twists on the standard conventions lead it to play out in outright confusing ways. Frye observes that the role of the senex (the old man/father) is reversed in this play. Whereas the father figure usually opposes the love affair in question (as in Egeus in Midsummer Night's Dream), the senex in this case, being the King, forces Bertram to marry Helena. As this concerns to storytelling and character development, the dynamic between these two "lovers" is a jarring one.

Why Helena, a lowly but gifted daughter of a physician, would be attracted to Bertram to the point that she goes through such extensive measures to woo him does adhere to our definition of courtship. Bertram is not a likable or relatable character. Some would say that he is revolting and detestable. And yet, when he rather coldly tells her that she will never truly be his wife via letter (probably the Shakespearen equivalent to a text message breakup), she still pursues him by attempting to secure his ring and his child, per his challenge. It's rather off-putting how much effort she goes through to marry below her in terms of her mate's moral character.

The convention of New Comedy pertaining to the wedding at the end is still intact, but once again, it feels out of place. Is it realistic to expect Bertram to accept Helena as his wife after he has been deceived with the elaborate "bed switching" plot?

If she, my liege, can make me know this clearly, / I'll love her dearly - ever, ever dearly. (V.3)It's a problematic situation, indeed. Realistically, why wouldn't Betram be further repulsed by Helena's troubling measures to woo him? By today's standards, the way that these two work together would be a compelling case study of a very unhealthy relationship. Bertram's submission to Helena's proposal is really the strongest point in which any sort of redeeming quality is apparent in his character, and it rings false.

Perhaps Shakespeare could have further skewed the conventions of New Comedy by having this realization on Bertram's part being quashed by Helena's realization that she deserves better. In a final act, she turns the tables and rejects him. Thus, the end would have no obligatory wedding that is a standard part of the New Comedy formula, but the majority of the cast would be present for what many readers/audience members would call justified humiliation. Sadistic? Probably. But to me, it makes more sense. Look at the myth of Venus and Adonis: the female is in the position to pursue the male. Adonis ends up meeting a brutal fate, and while this is far from comedic, one can argue that his rejection of the love of a goddess set him up for an untimely death. He did nothing to deserve her love, so why should he get it? In the case of Bertram, why the sudden change in heart?

What we're left with instead is a message that you can still be a terrible human being and wind up with a girl whom you've done nothing to deserve (unless being beaten at your own game of deception and impossible riddles makes you qualified). That's not to say that the word play and innuendos (as mentioned by Anne) don't give the play a humorous touch that makes it an interesting and clever play. Clever, but confusing... and not strictly in the Shakespearian sense.

Test tomorrow. Bring it on!

Monday, February 14, 2011

The Bible: "As (Shakespeare) Like(d) It"

I'm a bit of a mythology newbie myself. Before taking this class, previous experience exploring classical mythology being almost exclusively rooted in my 6th and 9th grade classrooms (yes, that long ago). Dissecting Shakespeare for the myth is something that admittedly doesn't come as intuitively to me as it does to others. However, here's my best crack at looking at Acts I & II of As You Like It. The first thing I noticed was stylistic--unlike Midsummer Night's Dream, the characters seem to speak in prose about as often as they shift into the lyrical sonnet style that Shakespeare uses so prominently.

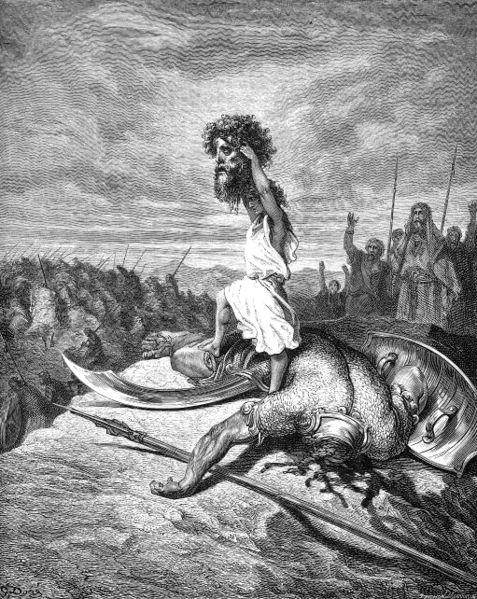

Another interesting bit jumped out at me when Orlando was pitted against Charles in a wrestling match. Charles, the duke's wrestler, was described in class as a "badass" of sorts. Orlando went into it as an underdog. Does this remind you of something? Well, it should.

True, no beheading took place in this instance, but Orlando's defeat of Charles is unmistakably a David and Goliath story. Orlando accepts the challenge and overcomes insurmountable odds against him to overcome Charles, with enough energy to spare as he cockily declares "I am not yet well breathed" when the duke calls the match to stop. Granted, Orlando is banished for victory and not lauded like David was, but you get the idea.

I'm really impressed with the quality of blogging going on in the class. While mine is not quite as high-brow as others, hopefully it effectively conveys what I like about Shakespeare and about As You Like It. The Bible with a twist--and I assume it only gets better.

My observations to Shakespeare's Biblical allusions may seem a bit trivial and obvious, but I found them to make for an interesting inclusion. In class, we already went over the big ones. The ever prevalent element of feuding brothers cannot be explored without considering the Cain and Abel. The banishment of Orlando and Duke Senior into the uncivilized forest of Arden ties back to God's banishment of Men from the Garden of Eden, etc., etc.

First off, pointing out the fact that the tension between Orlando and Oliver has ties to the parable of the prodigal son does not require much reading between the lines. Orlando speaks out against the pathetic conditions to which Oliver subjects him:

Shall I keep your hogs and eat husks with them? What prodigal portion have I spent that I should come to such penury? (I.1, 35-7)It's the prodigal son with a twist: Oliver subjects Orlando to life like a peasant, depriving him of the education and fortune promised in his father's will. Orlando pleads that age has no effect on the fact that he is as much Sir Roland de Boys' son as Oliver is, and that he is entitled to an inheritance that would liberate him from the grip that Oliver holds. It's the kind of reasoning that allowed the prodigal son in the parable to go out on his own, and arguably the father had this mindset when he welcomed the son home after taking a walk on the wild side. If I had to sum that rationale it up in a few words, I suppose they would be unconditional entitlement.

Another interesting bit jumped out at me when Orlando was pitted against Charles in a wrestling match. Charles, the duke's wrestler, was described in class as a "badass" of sorts. Orlando went into it as an underdog. Does this remind you of something? Well, it should.

True, no beheading took place in this instance, but Orlando's defeat of Charles is unmistakably a David and Goliath story. Orlando accepts the challenge and overcomes insurmountable odds against him to overcome Charles, with enough energy to spare as he cockily declares "I am not yet well breathed" when the duke calls the match to stop. Granted, Orlando is banished for victory and not lauded like David was, but you get the idea.

I'm really impressed with the quality of blogging going on in the class. While mine is not quite as high-brow as others, hopefully it effectively conveys what I like about Shakespeare and about As You Like It. The Bible with a twist--and I assume it only gets better.

Monday, February 7, 2011

Act V: Bringing it All Together

I'm a sucker for theater. At it's best, you're transfixed by something that makes no attempts to mask the artifice of the craft. It's almost like watching a movie, but made all the more exciting, hilarious, or emotional by the very notion that you're looking into a real scenario. There's an immediacy to theater that can't be replicated by technology, and thus, it's not going anywhere.

Now when theater is bad, it's bad. I mean really, really bad. You can typically tell within the first two minutes of a rotten play that you're in for an excruciating experience. And yet, I've always looked back on bad theater with a smile on my face--sure, the acting may have been awful and the blocking awkward as can be, but there's something a bit charming about when something goes horribly wrong on stage in spite of the best efforts of the players to make it good. I don't mean to sound like a sadist. I would much rather see a bad play than a bad film any day.

To expand a bit upon my contribution to my (enormous) group's presentation, Act V addresses an important notion of theater of reality and suspension of disbelief. Shakespeare can't be appreciated fully unless we acknowledge the fact that part of its liveliness and longevity lies in the performance of his plays.

Russ McDonald's preface to A Midsummer Night's Dream illuminates the notion of the play-within-a-play as a means to explore what is real:

Of course the breaching of the fourth wall at the end of the play is significant in supporting this idea. Puck's monologue tells the audience to merely forget what they have seen if the "shadows" on stage have offended them... wait, is it Puck or the actor playing Puck delivering the lines? Who knows?

In a play with the magic of otherworldly forces and imagination at work, Shakespeare carried the message to the end of the play in an exercise of self-awareness and metatheacricality. The players on stage (and us in the audience) may judge the mechanicals harshly for their amateurish production, but who then will be judging us?

I may come back and edit this when more comes to me... I'll think about it.

Now when theater is bad, it's bad. I mean really, really bad. You can typically tell within the first two minutes of a rotten play that you're in for an excruciating experience. And yet, I've always looked back on bad theater with a smile on my face--sure, the acting may have been awful and the blocking awkward as can be, but there's something a bit charming about when something goes horribly wrong on stage in spite of the best efforts of the players to make it good. I don't mean to sound like a sadist. I would much rather see a bad play than a bad film any day.

To expand a bit upon my contribution to my (enormous) group's presentation, Act V addresses an important notion of theater of reality and suspension of disbelief. Shakespeare can't be appreciated fully unless we acknowledge the fact that part of its liveliness and longevity lies in the performance of his plays.

Russ McDonald's preface to A Midsummer Night's Dream illuminates the notion of the play-within-a-play as a means to explore what is real:

Shakespeare's manipulation of perspective takes its most revelatory form in the arrangement of the play-within-the-play. During the performance of "Pyramus and Thisby", we may imagine the stage and the theater and the world as a series of concentric circles. At the very center are Bottom and Flute, playing tragic lovers. They are watched by actors playing the courtly lovers, characters whose experience might have paralleled that of the doomed Pyramus and Thisby but who fail to notice the similarity. They, in turn, are watched by the theater audience...Isn't it possible that we, too, are performing for unseen spectators... that the world we take to be real may be nothing more than a stage set for a divine audience? (pg. 255)The characters in the play are in a sense players for the amusement of the fairies. Oberon and Puck have their fun with them and when everybody is with the lover they are meant for, the events that happened before are merely dreams. Any uncertainties that the lovers possess aren't enough to lead them away from their newly found happiness in love. In a way, isn't the artifice of theater not enough to make us reconsider the experience we had with it?

Of course the breaching of the fourth wall at the end of the play is significant in supporting this idea. Puck's monologue tells the audience to merely forget what they have seen if the "shadows" on stage have offended them... wait, is it Puck or the actor playing Puck delivering the lines? Who knows?

In a play with the magic of otherworldly forces and imagination at work, Shakespeare carried the message to the end of the play in an exercise of self-awareness and metatheacricality. The players on stage (and us in the audience) may judge the mechanicals harshly for their amateurish production, but who then will be judging us?

I may come back and edit this when more comes to me... I'll think about it.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Book of Choice: "Northrop Frye on Shakespeare"

I chose Frye's book on a bit of a whim. It was available at the library and I thought, well, why not? Upon reading the introduction, I realized that I made a solid choice.

What I gather from the introduction is that Frye acknowledges the multidimensionality of Shakespeare's appeal and longevity. The fact that Shakespeare is a rare artist whose work transcends the time and culture of its creation is no revelation. And yet, Frye makes a compelling case that this fact of eternal relevance cannot overshadow the historical context in which it was written.

As somebody who is also a film major/theater junkie, I take interest in Frye's mention of the actual staging conventions and (for better or worse) versatility of the Bard's plays (i.e., changing the setting to Mars or Nazi Germany). The attention to detail in the creation of his characters also is something I look forward to reading about, as fully realized beings in the unique situations in which they exist. I believe that these components are very important and engaging, and while I do take interest in the more academic facets of Shakespeare studies (i.e., the references to classical works, etc.), I appreciate the fact that Frye says, "there is never anything outside his plays that he wants to 'say' or talk about in the plays."

I eagerly anticipate where this work may take me, and hope that it deepens my insight of Shakespeare. Here we go.

So wait a minute, who's the dude in the picture?

What I gather from the introduction is that Frye acknowledges the multidimensionality of Shakespeare's appeal and longevity. The fact that Shakespeare is a rare artist whose work transcends the time and culture of its creation is no revelation. And yet, Frye makes a compelling case that this fact of eternal relevance cannot overshadow the historical context in which it was written.

As somebody who is also a film major/theater junkie, I take interest in Frye's mention of the actual staging conventions and (for better or worse) versatility of the Bard's plays (i.e., changing the setting to Mars or Nazi Germany). The attention to detail in the creation of his characters also is something I look forward to reading about, as fully realized beings in the unique situations in which they exist. I believe that these components are very important and engaging, and while I do take interest in the more academic facets of Shakespeare studies (i.e., the references to classical works, etc.), I appreciate the fact that Frye says, "there is never anything outside his plays that he wants to 'say' or talk about in the plays."

I eagerly anticipate where this work may take me, and hope that it deepens my insight of Shakespeare. Here we go.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

A (Crude Attempt At A) Sonnet

Don't judge me too harshly for this. I'm telling you now that it will having to do with Shakespeare... I guess it's a sonnet on dreaming and sleep paralysis.

The moon's become a fickle friend.

Some nights are full of glorious peace,

And others never seem to end.

Insomnia, I ask that you disist and cease.

And yet when dreams my mind evokes

It feels like years in worlds abstract.

This rush of wonder an anthem provokes,

A song which holds this sense intact.

Yet there are times I can't escape

The confines of my nightly cell.

A ghostly bind holds tight like tape

My arms and legs, they can't rebel.

Though paralyzed in this brief fright,

The sleep is sleep, and that's just all right.

Meh... not bad.

The moon's become a fickle friend.

Some nights are full of glorious peace,

And others never seem to end.

Insomnia, I ask that you disist and cease.

And yet when dreams my mind evokes

It feels like years in worlds abstract.

This rush of wonder an anthem provokes,

A song which holds this sense intact.

Yet there are times I can't escape

The confines of my nightly cell.

A ghostly bind holds tight like tape

My arms and legs, they can't rebel.

Though paralyzed in this brief fright,

The sleep is sleep, and that's just all right.

Meh... not bad.

Monday, January 24, 2011

School of Night: A Whole Lot of Nothing

OK, first there's something I need to get out of my system.

Tell 'em, Billy!

Now, back to work.

Turner's essay struck me as a very interesting account of the luminaries associated with the cooler-than-thou collective of the School of Night. With the amount of times that the concept of "nothing" was brought up in one way or another, it would be easy to peg this group propagating a nihilistic view for the sake of rubbing it in the faces of the religious higher-ups. However, such an outlook would be far too boring... the way that the School of Night embraced this Nothing is something that I find fascinating and, in a way, inspiring.

Nothing at face value is obviously a huge disappointment. Look at the reaction to the discovery of the New World--once the honeymoon ended, Turner likens the societal reality that the supposed endless possibilities turned out to change nothing to the coming of a sickness. This promise of something grand turned out to be unfulfilled. The real excitement was one that couldn't be brought back to the masses--instead, this Nothing yielded intangible wonder and discovery that only the like of Thomas Hariot could grasp. Nothing that had to be experienced to be understood.

At the risk of sounding pretentious or sophomoric, what I took away from this essay is the limitless possibilities of Nothing. What we have to work with in the mind is without shape or form, and that if we should be so bold as to harness the energy of the void to make something, then anything can result. Now, not to pull the same "You can do absolutely anything that you want!" kind of stuff that everybody mother says to her child, but in reaching outside the bounds of convention, greatness ensues.

The section on Juan Vives' fable on the gods creating living creatures to act on the stage of the world encapsulates the weight that comes with manipulating but believing in this endlessness. This imitation that we as humans carry forth day by day, mimicking the gods (theoretically) yields creation and thought of great power. Sir Walter Raleigh said that the concept of the soul was something created, but that it was no less real for that fact... Now getting into spirituality and religion is kind of a slippery slope, but I agree with the thought that our attempts as humans to justify and explain our experiences--giving the intangible a definition--adds an element to it that helps us to understand it and maybe even look deeper into it.

I realize that this may be a lot of rambling. When I blog on my own time (not very often), I tend to ramble on and on... I'm not terribly used to doing this academically but I hope that this entry wasn't a total insult to Turner's insightful writing.

I realize that this may be a lot of rambling. When I blog on my own time (not very often), I tend to ramble on and on... I'm not terribly used to doing this academically but I hope that this entry wasn't a total insult to Turner's insightful writing.

Consuming Myths--David Bowie Style

Hey, all.

The discussion on consuming myths got me thinking about a haunting song from David Bowie's classic album "Low". While I don't know if this myth necessarily consumed Bowie, it's a creepy thought--no matter what you do or how you look ahead, you're bound to make the same mistakes as before. I suppose we have all felt this at some point.

I'm sure this is addressed more eloquently in some classical work, but until I learn what this is, this will do.

The discussion on consuming myths got me thinking about a haunting song from David Bowie's classic album "Low". While I don't know if this myth necessarily consumed Bowie, it's a creepy thought--no matter what you do or how you look ahead, you're bound to make the same mistakes as before. I suppose we have all felt this at some point.

I'm sure this is addressed more eloquently in some classical work, but until I learn what this is, this will do.

"Always Crashing in the Same Car"

Academically substantial discourse to follow, I swear!

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Venus and Adonis/The Rape of Lucrece

Being a bit of a Shakespeare newbie myself, I was not familiar with either poem before I read them. I found them both to be very interesting takes on a totally one-sided sexual encounter--one obviously more sinister than the other.

Overall they were both fascinating reads and made for compelling companion pieces to each other. What did you all thing?

Maybe I just need to read more Shakespeare and classical lit, but the "girl chases guy" aspect of Venus and Adonis was something that I had never quite read before in this sort of mythical context. The notion of the male being the innocent virgin was an interesting take on it. Maybe not virgin in the totally pure and virtuous sense... but he literally has no interest in Venus and calls love "a life in death". In a way he seems to have the right idea, knowing that it wasn't worth his time and that he would eventually die soon anyway.

The Rape of Lucrece was a pretty unsettling read for me. Tarquin's seemingly endless internal monolog about his motivation to commit such a horrible and unforgivable crime is pretty dark, and it seems pretty ahead of its time in execution and subject matter. He wasn't a one-sided "Snidely Whiplash" type character but rather one with some pretty deep and disturbing motivations. Lucrece's devastation also seems quite real and powerful, even though the fact that her revenge can only be completed by committing suicide is quite tragic.

Overall they were both fascinating reads and made for compelling companion pieces to each other. What did you all thing?

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Billy Shakespeare and Me.

I'd be surprised to hear if I was the only one whose first introduction to Shakespeare was freshmen year in high school, reading "Romeo and Juliet" in English class. In a way it's totally appropriate--awkward teens in their transitional years reading about other awkward teens who probably weren't to smart about who they were fooling around with. Reading that in class and watching the Franco Zefferelli film version made for an overall satisfactory intro to Shakespeare. Then came "Hamlet" in sophomore year and "King Lear" senior year (each of them read at least once more in college).

I don't think I grew to actually appreciate Shakespeare fully until taking Walter Metz's MTA 104 "Theater and Mass Media" class in fulfillment of my film major. "Hamlet" and "The Tempest" were both readings on the syllabus, and the way Walter taught the class was in such a fashion that really opened my eyes to the theatrical roots of just about any form of popular medium today--specifically film and television. The fact that Shakespeare's fingerprints are all over everything from "Gilligan's Island" (Walter was convinced that the castaways' five minute staging of "Hamlet" was probably the most concise and clever adaptation of all time) to South Park ("Titus Andronicus" = "Scott Tenorman Must Die"...seriously) speaks a lot to the power and life present in his works. It was a very rich experience and helped me see that Shakespeare was pretty much present in the DNA of any pop culture entity.

There was a funny article on The Onion.Com about a bold, revolutionary director of Shakespearean theater who was directing one of The Bard's plays in the time and setting that the playwright intended. As a student of film, storytelling, art, and literature I think the fact that Shakespeare has never really become irrelevant is really mindblowing. I'm looking forward to hearing aaaaaaall about it.

I don't think I grew to actually appreciate Shakespeare fully until taking Walter Metz's MTA 104 "Theater and Mass Media" class in fulfillment of my film major. "Hamlet" and "The Tempest" were both readings on the syllabus, and the way Walter taught the class was in such a fashion that really opened my eyes to the theatrical roots of just about any form of popular medium today--specifically film and television. The fact that Shakespeare's fingerprints are all over everything from "Gilligan's Island" (Walter was convinced that the castaways' five minute staging of "Hamlet" was probably the most concise and clever adaptation of all time) to South Park ("Titus Andronicus" = "Scott Tenorman Must Die"...seriously) speaks a lot to the power and life present in his works. It was a very rich experience and helped me see that Shakespeare was pretty much present in the DNA of any pop culture entity.

There was a funny article on The Onion.Com about a bold, revolutionary director of Shakespearean theater who was directing one of The Bard's plays in the time and setting that the playwright intended. As a student of film, storytelling, art, and literature I think the fact that Shakespeare has never really become irrelevant is really mindblowing. I'm looking forward to hearing aaaaaaall about it.

Truly not the end of zombie Shakespeare.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)